How much is my life worth?

That was the question posed over 35 years ago at a Faith Builders’ sponsored colloquy on healthcare. How much is an acceptable amount of money to spend on my own health?

Obviously, we can’t find that answer directly in Scripture, and the answer we do land on is going to vary from person to person. The purpose of this essay is to outline some general principles which are consistent with Biblical values.

Since I am not a proponent of insurance-driven healthcare (for those who don’t know, we operate a “cash practice”1), I discuss the economics of health with my patients on a daily basis. Just this week I was doing a preoperative clearance on a patient for a planned orthopedic surgery. However, I included this caveat: the quoted self-pay price is 3+x the national average for this surgery, and I therefore advised patient to not proceed until a better price had been negotiated. Another patient from this past week told me that a cardiologist had recommended a certain medicine because of its cardiac benefits. When asked about the price, the doc didn’t have any idea. (It’s a $500 to $1,000/month med.) I’ve read that some physicians feel it’s unethical to discuss pricing with patients. For me, it’s unethical not to!

Let me also differentiate between terminal versus chronic illness. Terminal illness means there is no known cure outside of a God-directed miracle and death is likely imminent in the not-too-distant future. A 2014 study of doctors showed that 88% would choose DNR (do not resuscitate) for themselves when faced with a terminal illness in contrast to what they might recommend for their patients.2 Chronic illness, on the other hand, may also not have a cure but subsequent death is not on the near horizon. This is much more challenging when it comes to allocating healthcare dollars.

Biblical Principles

Let me begin with one of the most striking verses in Scripture in terms of our allotted days (Psalm 139:16, ESV):

Your eyes saw my unformed substance;

in your book were written, every one of them,

the days that were formed for me,

when as yet there was none of them.

Unformed substance in Hebrew is literally formless mass or embryo. The image is our allotted days being inscribed on a scroll. The idea is that the life stages of the psalmist were predetermined. In The Grammar of the Psalter, Mitchel Dahood (an American Jesuit Hebraist who died in 1982) writes3:

Like the Servant (Isa 49:1, 5), Jeremiah (1:5), and the Apostle Paul (Gal 1:15), the psalmist was predestined; his life stages and his days were decided and counted even before he was seen by them.

A friend of mine once told me, “You doctors can’t do anything to lengthen someone’s life.” This was in the context of why he was not getting a colonoscopy! I internally bristled, but then I came back to the above verse. It’s pretty clear!4

Within this context, it’s worth heeding the advice of King Solomon, the wisest man who ever lived. Certainly, Ecclesiastes reminds us that there is a lot of “vanity” or futility in chasing after work, wealth, and pleasure. Yet it also surprisingly hopeful in its admonition to enjoy life (see 9:7-10, for example) within the context of God’s laws (“fear God and keep his commandments” [12:13]), with the understanding that all will be judged by God in the end (12:14). Considering that his daily court alone required about 180 bushels of wheat and 360 bushels of meal (I Kings 4:22), I doubt that his diet was gluten-free! And given the daily requirement of “ten fat oxen, and twenty pasture-fed cattle” (4:23), it likely wasn’t fat-free or dairy-free either!5

This is reminiscent of the New Testament reminder (Hebrews 9:27, KJV):

And as it is appointed unto man once to die, but after this the judgment.

The Letter of James (4:14, ESV) reminds us that in the midst of advance planning for life and business,

…you do not know what tomorrow will bring. What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes.

In the Big Scheme of Things, our lives are compared to a transient mist that’s burned up by the morning sun. The following verse reminds us that our plans must be set in the light of Deo volente (D.V.), “if the Lord wills.” John Wesley reflected in his journal on this passage as he waited at Chester near the Irish Sea for favorable wind to sail to Ireland:

James would have approved the spirit of this entry, … contrasting as it does with the presumption of those he rebuked who planned the future without regard to the will of God or the uncertainties of life. What James urges is not a morbid preoccupation with possible disaster, but a realistic attitude to the future made possible by faith in God.… Realizing the future is uncertain not only teaches us trust in God, it helps us properly to value the present. To be obsessed with future plans may mark our failure to appreciate present blessings or our evasion of present duties.6

In one of the most convicting passages to me as a physician, we read in Mark (5:25-26, ESV) of the woman who had a presumably menstrual bleeding disorder:

25 And there was a woman who had had a discharge of blood for twelve years, 26 and who had suffered much under many physicians, and had spent all that she had, and was no better but rather grew worse.

Spent all that she had. No better, but actually worse! What a commentary on failure of care! But it does get at the heart of the question—how much is my life actually worth?

Bioethical Principles

Beauchamp and Childress first published their Principles of Biomedical Ethics in 1979. Currently in its 8th Edition, this text outlines four universal principles which help guide decisions in biomedical care. While not explicitly Christian, they have universal appeal and application regardless of faith.

Nonmaleficence: Since Hippocrates, the first principle of medicine has been primum non nocere, or “first, do no harm.” While stated in the negative, it is a daily guiding principle in my practice. I always need to make certain that anything I prescribe or recommend is not going to cause harm. If it doesn’t (cause harm), then it’s passed the first test.

Beneficence: This is the positive other side of the coin, which I loosely translate as “do some good.” Because it’s not enough to just not harm. We would expect that therapeutic recommendations would actually do good. If we can’t be certain that it will do good, then caution is advised. It seems simple enough, but it’s amazing how often both of these principles get overlooked in medical care!

Autonomy: Medicine used to be very paternalistic, as in “I’m the doctor and you do as I say.” When I was in training, the emphasis was very much on patient-centered care. Options were given and the patient chose. During Covid, there was an extreme swing back to paternalism in the form of mandates and patient dismissal from practices for failure to comply. But this hallmark principle has always emphasized a “patient first” philosophy with the patient in the driver’s seat.

Justice: Perhaps the hardest to wrap one’s head around, this is best translated as “the greatest good for the greatest number.” It’s this principle that guides the use of finite medical resources. For example, if there are 10 people and $1M, is it ethical or wise to spend $900k on 1 and $100k on the other 9? This principle rightly stands in tension with autonomy. This is why there are advisory boards on healthcare sharing plans to provide guidance on allocation of resources.

Gelassenheit: An Anabaptist Ideal

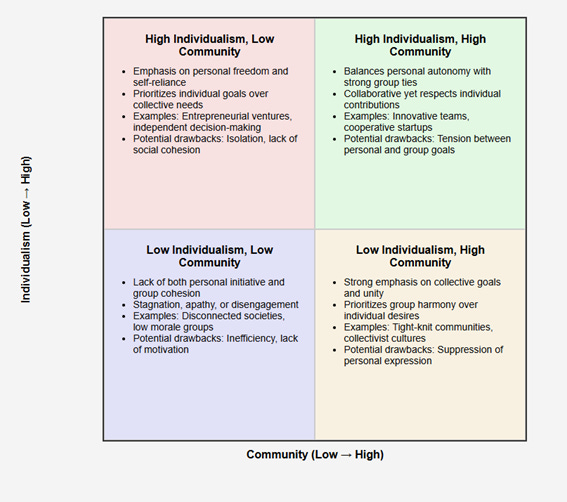

It’s worth pondering another tension, and that is the relationship between individualism and community with respect to emphasis.

Entrepreneurs tend to be highly individualistic. They are often risk-takers in spite of community.

The American frontier was conquered through a spirit of rugged individualism combined with community survival.

Many religious groups (the Anabaptists, for example) thrive because the community takes precedence over the individual.

Loners and sociopaths are born through a lack of both individual and community initiative. These can be described as “the dropouts of any generation.”7

I asked Grok to create a Punnett square expressing this, and after several tries, here was the result (above description is clockwise from top left).

I want to flesh out the bottom right a bit more using the Anabaptists as an example. Snyder writes:

Persons in the low individualism-high community group are members of a community. Their satisfaction in life derives from that membership. Their own individual achievement is not very important, nor does the achievement of the community insure [sic] individual satisfaction. Belonging is much more important. One is somebody (and therefore an individual) simply by belonging. The community forms the individual and protects its members.

Individuals will be healthy as long as they belong, whereas ill health derives from rupture within the community. Historic Anabaptists speak of Gelassenheit, or submission, as an essential characteristic for community life. Brethren speak of humility…8

Gelassenheit is a difficult term to define. A direct translation from German will yield something like “serenity” or “composure.” But that is a pretty vanilla description! It’s been suggested that it has as many as fifteen different translations. The ones that get to the heart of what I’m describing are self-surrender, self-abandonment, letting go, and resignation and yielding to God’s will.9

This coexisted in the context of Gemeinschaft, or community, better interpreted as “living and, if need be, suffering together as a fellowship of dedicated disciples.”10 This often involved the image of many kernels of wheat coming together in one common loaf of bread.

These concepts are embodied by Jesus’ prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:42, ESV):

Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done.

It is further exposited in the Apostle Paul’s description of Christ in Philippians 2 (ESV):

5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus,[a] 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped,[b] 7 but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant,[c] being born in the likeness of men. 8 And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.

This kenosis or emptying of Himself is the ultimate yielding to the Father’s will. We are instructed to have this same mind, which is truly countercultural to the potential selfishness of individualism.

Summary Points

Obviously, we can’t set a dollar amount to the question posed in the title. However, I believe the principles outlined above will provide some very clear directives. Let me offer three simple practical applications.

Utilize the value of community when the individual direction is unclear. We were never meant to navigate life alone. Consider creating a team or support group for challenging individual cases.

Reassess the big picture. Remember where you’ve come from, evaluate where you are presently, and assess where you are going. You will probably need others to help with this process.

Don’t chase every pot of gold at the end of every rainbow! There are people who make their living crafting compelling narratives—which are false! Pray for discernment.

Finally, realize that the earthly vessels we dwell in are the temples of the Holy Spirit, but they are transient. Someday a minister will stand at our graveside and proclaim, “Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”11 We are sojourners in this vale of tears, strangers and pilgrims seeking our Heavenly Country. “For here we have no continuing city, but we seek one to come” (Hebrews 13:14, KJV).

Even so come, Lord Jesus!

Dr. Yeager’s reflections on goodness, truth, and beauty and their impact on life, medicine, and theology; what it means to live as male and female reflections of the imago Dei (Genesis 1:27); not intended as individual medical advice.

I outline the reasons for this in my 2018 book Transforming Healthcare Together: A Model for Restoring the Covenant of Trust, available here.

Mitchell Dahood S.J., Psalms III: 101-150: Introduction, Translation, and Notes with an Appendix: The Grammar of the Psalter, vol. 17A, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 295–296. (From Logos.)

A slightly trickier question (which involves sovereignty and free will) is whether I can shorten my life. For example, I could choose to walk across our busy Route 419 in front of an 18-wheeler.

I am not denigrating anyone who follows these diets. I would point out that there is a several thousand-year-old wheat called einkorn, and gluten-sensitive people can use this wheat with no symptoms (so I’ve been told). I do believe our modern diet has strayed very far from Biblical parameters, and our foodstuffs are flagrantly adulterated. This is why I emphasize growing and eating your own whole foods.

James B. Adamson, The Epistle of James, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1976), 179–180. As cited in 80a The Armoury Commentary: The NT Epistles (1975), p. 271. (From Logos.)

Graydon F. Snyder, Health and Medicine in the Anabaptist Tradition: Care in Community (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1995), p. 20.

Ibid, p. 21.

Friedmann, Robert. “Gelassenheit.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1955. Web. 12 Oct 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Gelassenheit&oldid=162946.

Friedmann, Robert. “Lord’s Supper, Anabaptist Interpretations.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1957. Web. 12 Oct 2025. https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Lord%E2%80%99s_Supper,_Anabaptist_Interpretations&oldid=102731.

There are various renditions of this, but these are the general words from the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer: “Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother [sister] here departed: we therefore commit his [her] body to the ground; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life, through our Lord Jesus Christ; who shall change our vile body, that it may be like unto his glorious body, according to the mighty working, whereby he is able to subdue all things to himself.”